How to Write like Ernest Hemingway

A legendary artist's framework for boundless creativity.

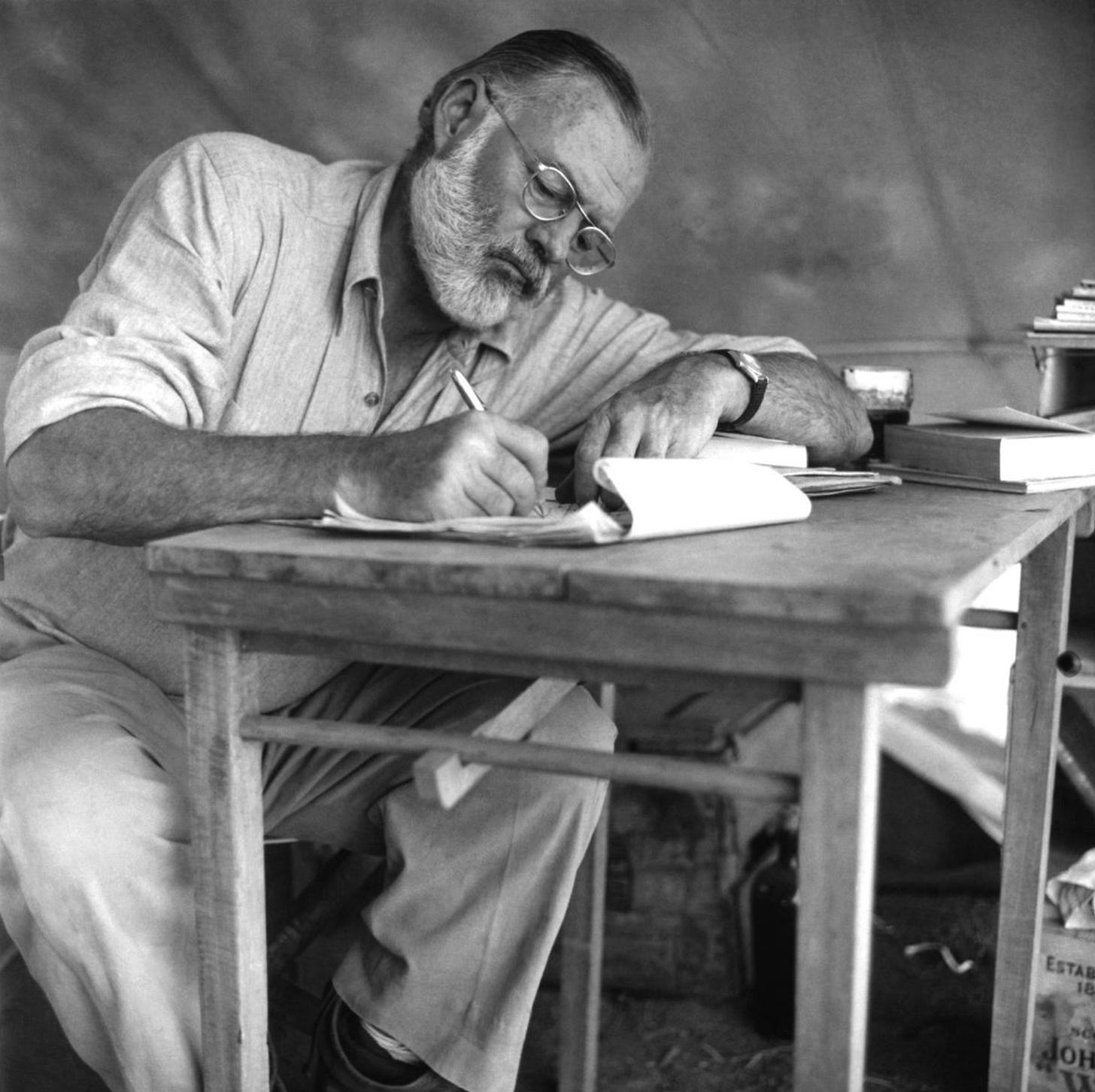

Ernest Hemingway lived to write.

He packed entire lifetimes into decades. He saw three major wars up close. His body carried the fractures and scars of multiple scrapes with death. By the time he invited it, at only 61 years of age, he had revolutionized American writing.

But how did he achieve such outstanding results?

By the end of this short article you’ll have a window into the creative process of one of the greatest writers who ever lived—and a framework with which to attack whatever project you’re working on (including a spectacular tip for destroying writer’s block).

You’ll never run out of ideas again.

EXPLORE YOUR SENSUALITY (A PROLOGUE)

Stop living on social media. Get unstuck from the news cycle. Stop grousing about the state of the world, cradling your smartphone from sunrise to sunset, and numbing yourself with cheap dopamine. Such counsel is cliché and obvious to many, but for creatives it is essential.

Become present in the world, not numb to it. Its sights, sounds, smells, tastes. Savor them. Remember how they make you feel. Experience living in richer detail. Normal people spend their lives trying not to feel; the artist has no such luxury.

Joy and sorrow, sexual ecstasy, furious rage—these are not to be repressed but integrated. These sensations—pleasurable and painful—remind you that you are alive. You must leave the channels of experience as open as possible.

That will make it easier to...

FILL YOUR “WELL”

Hemingway: A writer can be compared to a well...The important thing is to have good water in the well.

When asked about who he’s learned the most from, Hemingway rattled off a list of artists that included not just writers (Shakespeare, Chekhov and Mark Twain), but painters (Cezanne and Van Gogh) and composers (Bach and Mozart).

Pulling inspiration from all corners was a no-brainer:

“I should think what one learns from composers and from the study of harmony and counterpoint would be obvious.”

We are blessed and cursed to live in an era of constant stimuli. There is inspiration everywhere—and more than enough “slop.” Therefore it is crucial for the artist to curate the quality of what he consumes.

Fill your reservoir—your “well”—with meaningful material. Rich music, moving cinema, great literature, penetrating nonfiction, incredible paintings, dance, drama. Never fail to enrich yourself with the genius of others, for that is truly inspired living.

Moreover, your world will drastically improve as your personality deepens. Over time more layers will accrue within you. You’ll develop a depth of emotion and sophistication of which you never knew you were capable. You’ll bring this newfound texture into your relationships, into your work, into each aspect of your life.

You’ll set yourself apart from everyone else.

SET A STRUCTURE

Hemingway: When I am working on a book or a story I write every morning as soon after first light as possible. There is no one to disturb you and it is cool or cold and you come to your work and you warm as you write.

Non-artists and hacks believe that creatives laze about, and wait for inspiration to strike before they can work. Of course, Hemingway—and any great artist—knows this is absurd.

This write up by George Plimpton gives insight into the discipline with which Hemingway attacked his work:

...early in the morning Hemingway gets up to stand in absolute concentration in front of his reading board, moving only to shift weight from one foot to another, perspiring heavily when the work is going well, excited as a boy, fretful, miserable when the artistic touch momentarily vanishes—slave of a self-imposed discipline which lasts until about noon when he takes a knotted walking stick and leaves the house for the swimming pool where he takes his daily half-mile swim.

The above was written after Hemingway had cemented his reputation as one of the 20th century’s most important writers.

The true artist never stops working. To do so would be the same as death.

But here’s an interesting counterpoint:

STOP BEFORE YOU’RE FINISHED.

Hemingway: You write until you come to a place where you still have your juice and you know what will happen next and you stop and try to live through until the next day when you hit it again...if you stopped when you knew what would happen next, you can go on. As long as you can start, you are all right. The juice will come.

This may be Hemingway’s most powerful idea.

You’ve developed your sensuality. Your “well” is full of quality water (or “juice”). You’re bursting with vitality and ideas, and have a system in which to apply them. The temptation now might be to implement all your ideas at once, to work to exhaustion. To Hemingway, this was counterproductive.

He would stop the day’s work before he was drained dry, so he would have something to look forward to the next day. This avoids the anxiety of “running out of ideas,” counteracts the dread of having to restart the engine at the next session, and runs counter to the endless churn of “Hustle Culture.”

When you leave the work behind, it still lives within you. There is no need to tend to it. Your psyche will continue to grapple with whatever creative problem you’re working through. Trust it, and attack the next day’s work fresh, bursting with new energy—and even more ideas.

And you’ll never run out of “juice.”

EPILOGUE

It’s neither necessary nor advisable to find wars to fight in (although you’re in one right now).

Hemingway was an extraordinary man, who lived through extraordinary times. But his brilliance as an artist belies a simple, repeatable approach to process that anyone can incorporate into their lives, whether the nature of their work is creative or corporate.

Anyone can live more sensually, fill their “well” with quality “water,” incorporate a disciplined approach to their work, and stop before they run themselves ragged.

That means you, too.

Now go forth:

Become unforgettable.

CD

Great stuff. Did Hemingway also say get rid of openings, prologues or preliminary scene-setting -- dive into the story when it's already underway (first paragraph of "Fifty Grand," a lean, elegiac boxing vignette, for example)? That strategy seems related to Hem's tip to quit while there's ink in the pen for the next morning's stint, somehow, but how? Is it a knack for not overdoing, a technique for persistence by pruning? Not sure, but loved this post. Yes, Hemingway's still a giant, and his discipline an inspiration. Do you hear a Sowellian note in Hemingway's bluff, spare, unhurried but direct way of framing sentences and paragraphs? Is there an affinity in the beautiful lucidity -- and the wit that goes along with their wisdom -- of both writers' way of handling English, in their different genres? Did Sowell read Hemingway?

You are 100% right my friend. Great advice. Our electronics are disconnecting us ever more from the world and each other. There is no "human experience" on the little black mirrors.